Work is constantly evolving but technological and social changes are accelerating certain aspects of work. Working from anywhere has exploded since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic and does not look like it will disappear. The digital workplace requires unique skills in collaborating in distributed teams and cooperating in knowledge networks.

The most recent technology to influence how work gets done is artificial intelligence — specifically generative large language multi-modal models (GLM). The rate at which these new technologies are being integrated requires agile sensemaking from workers adapting to the changing human-machine work interface. It is highly likely that the pace of change will continue and even accelerate.

While we cannot predict the future of work or know how GLMs will develop, we can assess what human meta-skills are necessary to individually and collectively understand working with smart machines. There are three meta-skills that can help us adapt to a future of work with smart machines.

- Learning ‘How’ to Learn — curiosity & the resolve to solve problems

- Adapting to Change — agile sensemaking

- Collaboration & Cooperation — knowledge-sharing

Learning ‘How’ to Learn — not ‘What’

Learning how to learn is making sense of the environment and using this knowledge to take action.

We learn from experiences and exposure to people and ideas. Social networks can provide inspiration but sensemaking requires the resolve to solve problems. This means the integration of learning and working.

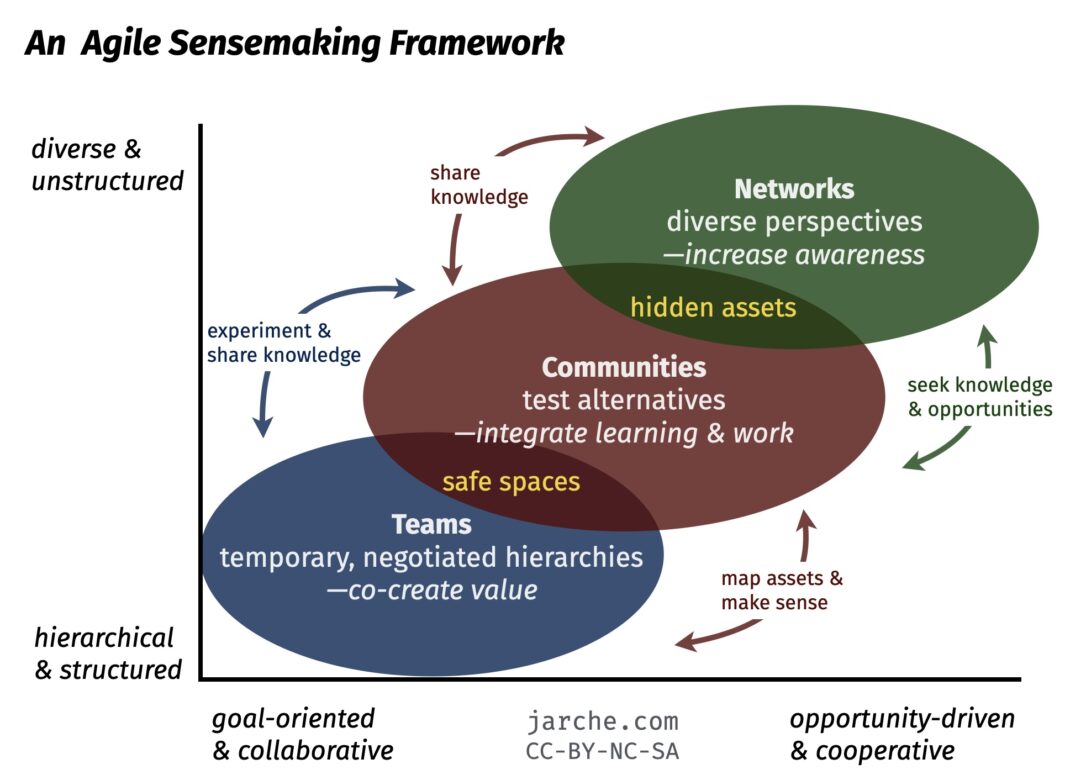

Flipping from learning to working is a continuous process on a daily basis. Everyone has to seek to understand their environment, seek and make sense of new ideas, make sense of practical experience, and share new practices — continuously. We learn from our teams, our communities, and our knowledge networks.

A core skill is curiosity. Curiosity about ideas can foster creativity, while curiosity about people can develop empathy (not sympathy). We get new ideas from new people, not the same people we see every day. We get new perspectives from people whose lives and experiences are different from ours. We cannot be empathetic for others unless we are first curious about them. We cannot be creative unless we are first curious to learn new ideas.

Networks are made up of nodes (people) and relationships between them. Curiosity and learning can create new connections between people and ideas. Constantly learning fractal beings can make for more resilient knowledge networks.

Curiosity yields insight.

It starts with curiosity and humility.

Adapting to Change

Much work today is in a state of perpetual beta — adapting to constant change while still getting things done.

The human work that is emerging from increasing automation is complex and creative. In complex environments, emergent practices need to be developed while simultaneously engaging the problem. Social learning is the best medium for groups of people to cooperate and learn with and from each other. As discourse augments formal training, social learning in knowledge networks becomes a critical skill in order to adapt to a changing work environment.

New methods and practices — often ‘just good enough’ — have to be developed, used, modified, and eventually discarded as the nature of the work changes. The only way to stay ahead of the machines will be by using our unique human capabilities. In addition, people will have to understand how the machines and algorithms work, to ensure proper human oversight.

Developing the skills of a knowledge artisan in every field of work are critical for success. While getting work done collaboratively will continue to be of importance in all organizations, it will not be enough. New ideas will have to come from external professional networks in order to keep pace with innovation and change in all fields.

Safe places are needed to connect new ideas to the work to be done — communities. The need for communities of practice continues to grow as knowledge artisans look for places to integrate their work and learning in a trusted space. As the gig economy dominates, communities of practice can bring some stability to our professional development. These are owned by the practitioners themselves.

Agile sensemaking could be described as how we make sense of complex challenges by interacting with others and sharing knowledge. More diverse and open knowledge flows enable more rapid sensemaking.

Collaboration & Cooperation

Work in networks requires different skills than in directed hierarchies. Cooperation is a foundational behaviour for effectively working in networks, and it’s in networks where most of us will be working, if we are not already. Cooperation presumes the freedom of individuals to join and participate, so that people in the network cannot be told what to do, only influenced. If they don’t like you, they won’t connect. A lone node is of little value to the network. In a rigid hierarchy you only have to please your boss. In a network you have to be seen as having some value, though not the same value, by many others.

Cooperation is not the same as collaboration, though they are complementary. Collaboration requires a common goal while cooperation is sharing without any specific objectives. Teams, groups, and markets collaborate. Online social networks and communities of practice cooperate. Working cooperatively requires a different mindset than merely collaborating on a defined project. Being cooperative means being open to others outside your group.

Effective knowledge networks are composed of unique individuals working on common challenges, together for a discrete period of time before the network shifts its focus again. We must move from a ‘one size fits all’ attitude on work and learning to an ‘everyone is unique’ perspective. The network enables infinite combinations between unique nodes.

This connectivity is already resulting in an increasing number of discoveries from non-traditional areas, as we have witnessed in the rapid development of vaccines during this pandemic. In a networked workplace, where everyone is unique, there is a diminishing need for generic work processes (jobs, roles, occupations) and for standard curricula.